I guess this is going to come down to agreement, or not, on whether what you describe (which I'd agree with by and large) is a fundamental change.

Sure the context is different, but the context that Marx wrote Capital in was different to the context of the agrarian development of capitalism, it was different to the period from the turn of the 20th Century to WWII, and different from the post was period. Capitalism changes, but it remains capitalism, for me the fundamental nature of class relations persists.

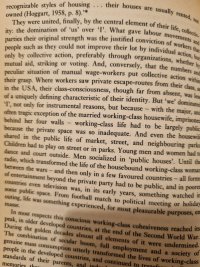

Just been reading The Age of Extremes by Hobsbawm and this passage struck me as telling about what has changed. I can't be bothered to write it out myself so I took a photo of the pages which you can read as the attachments below if you are interested.

He basically describes how "we" dominated "I" in working class communities, as inadequate living space meant they had to live their lives publicly, socialising publicly, kids playing on the streets... but TV meant you no longer had to go to the football match in person when you can watch on TV, and the social attraction of a union meeting also subsided as people got more distractions at home, and the telephone meant people could gossip from home without going to a public place for the sake of chatter.

Hobsbawm doesn't mention this but my dad always described how back then everyone would get the same bus into work together, take lunch together, and so on. In my dad's words, working in a factory turned you into a Communist.

The core nature of the class relation may not have changed, but the means in which class consciousness is generated has faded. True, working class people still have less space but people live much more individualised lives now. There are no more mass employers or factory towns and people's working lives and social lives are much more diffuse so it is harder to build a true sense of "we".

There are also other things which have obfuscated the class relationship. As others have said, dependence on private pensions (and also things like employee share purchase plans) give people who would otherwise be proletarian a material interest in share prices or property values. Some of this is deliberate social engineering, e.g. Thatcher's sale of council housing, and employee share purchase plans is clearly a means by the employer to get employees to think in terms of shareholder value.

The third factor is globalisation, strike action has lost the potency it once had when the bosses can respond by growing their branch in India.

I don't know what the answer is if you hope to overthrow capitalism. But I feel that we have to rethink things.

The only ideas I can think of is that the things which divide us from the localised "we" of 20th Century working class movements can be turned into something that creates a new "we" of the internationalised working class. The revolution in telecommunications has separated us more from our neighbours and communities but it has potential to link us to millions in all corners of the world. Globalised capital has blunted the bargaining power of labour but it has also created the seeds of a truly internationalised labour movement.

I don't know how this is going to happen, but I think building something international is something the left should be focused primarily on. I was briefly involved with Yannis Varoufakis" DiEM25 movement (my sister and her boyfriend were much more heavily involved) which I thought was a good idea to build a transnational political party but in practise it was extremely difficult to get off the ground because of laws regulating international financing of political parties which makes it extremely difficult to organise internationally in a credible way. But I feel like there are ways around this with the right sort of cleverness and trickery.

I'm convinced that managing to build a kind of transnational political party with a unified brand (symbols are, like it or not, powerful mobilisers of collective action and identity) which takes full advantage of all our means of telecommunications to bring together disparate perspectives into a common universal program while also being decentralised and federal enough to reflect differences in local conditions would serve as a kind of lightning rod to bring together the emergence of a new kind of "us" identity, which is proletarian but also cosmopolitan and globalised, tech-savvy, cutting edge, subversive, and sexy, something which people feel excited to be a part of. Maybe it has to be not just a political party but also a kind of social media and global community. I think use of AI translation tools which are just within reach open up new possibilities for ordinary people being able to converse in real time without a shared language, something as historically unprecedented as the printing press was so why shouldn't it be as politically explosive as that was as well?

It won't resemble the worker's movements of the 20th Century but I think that trying to revive them by the same means is doomed to failure and we should be aspiring to create something new or at least thinking of a new approach.